I want to say right here that I have never been able to make a paper airplane that will fly. It’s just one of those skills that has always eluded me. I have known a few children who possessed this ability to an impressive degree. One first grader, Siraj, was so good that I sent him to the paper airplane-palooza, an event usually just for our fifth graders. Siraj was born in Iraq. He didn’t speak very much English at the time, but was learning quickly and overcoming his shyness. He’d spent most of his kindergarten year observing a studious silence, taking in everything around him in our busy, urban school. When he discovered that his airplane building was something impressive to his teacher, he became extremely enthusiastic about explaining to me how he did it.

This turning point for Siraj made me think of another child I had worked with while still a student teacher. I had been placed in a fourth- and fifth-grade special education class and had a few extra hours between classes. When I asked if there was another spot onsite where I could be of use (and also learn a bit more) it was suggested that I try the resource room. Resource specialists are specially qualified teachers who take students out of their regular education classrooms to give them extra one-to-one support. The specialist had a heavy load of students and was glad to let me work with some of them for a couple of hours each week. One fifth-grade boy, Binh, was to be my special project.

In general, students are only assigned to resource support if they have an individualized educational program (IEP). I don’t remember whether Binh actually qualified for special education services. What I do remember is that he seemed to be a frustrated student who had been getting into trouble in class. Evidently, he had been too much for his teacher, who was nearing retirement. Binh was a newcomer to the States and his English skills were minimal. I was assigned to help Binh learn to read. We were given some first grade reading materials to work with, including a couple of storybooks like Curious George. Now, I have nothing against the little monkey, though I have wondered from time to time about the man in the yellow hat. Our problem was that Binh had absolutely no interest in these materials. He said Curious George was a “baby’s book”.

After a couple of nearly hopeless sessions where Binh mostly yawned and fiddled around, looking for ways to giggle away the tension, I asked the resource teacher if she could tell me anything about Binh’s interests. She told me all he ever wanted to do was make paper airplanes. It was a place for me to start. The next time I came in to work with Binh I asked him to show me how he did it. At first he didn’t seem to trust my request. He stared at me and furrowed his brow. “No, really, show me,” I said, sliding a fresh sheet of paper across the table to him. Binh set to work immediately. With a series of precise folds he created a fabulous, elaborate paper plane. Then he sent it flying through the narrow, dusty old room. It soared up and across, almost to the windows. I laughed and looked around, making sure no one was watching what would surely look like horseplay on the part of an extremely green student teacher and her recalcitrant charge.

“Binh, you have to explain it to me. How do you do it? Tell me every step.” I had him start over and show me each fold in his beautiful, complicated creation. As he explained, I asked as many clarifying questions as I could think of. Being so unskilled at these things myself, I was the perfect student for Binh. As our 40-minute period together was ticking away, I decided we’d better get some work done with Curious George. Then I asked Binh to let me take the plane with me. (I didn’t want him to go back to class with it and get us both in trouble.)

After I got home I couldn’t stop thinking about Binh. There had to be a way to give him a more interesting way into the language skills he needed for school. Then I hit on the idea of an airplane maker’s manual. I got a small spiral notebook and several sheets of bond paper. The next time Binh and I got together, we talked a little and reviewed some of the vocabulary and other stuff we were supposed to cover. Then I told Binh about my plan. He seemed pretty skeptical, but I was getting used to his initial displays of reluctance. I showed him the notebook and had him put his name on it. Then we discussed a title. To Make a Wonderful Plane, was his ultimate choice. I helped Binh spell out his title on the cover and on the title page, along with the date and the name of his school. I was determined that we’d be making a wonderful book.

My meetings with Binh were only twice a week for about forty minutes. Each time we got together we’d work on the book. As Binh made the first fold, I stopped him and asked him to explain exactly what he’d just finished doing. I repeated back his directions and asked for more information. (“Pretend the person reading your book is not very smart about these things. Pretend it’s someone who didn’t see what you just did. Do you start with the paper long-ways? Do you fold it towards you, like this?”) I helped him write down just that much information on the first right-hand page. Then we glued the paper with its first airplane fold onto the left, facing page. We were painstakingly methodical about our process. Binh would explain one step per page. For each new step, he would construct a plane up to that point and we’d glue it down on the left.

We hit a few walls along the way. At times Binh became frustrated with me. I must have seemed very dense, constantly asking for more clarification, more information. Eventually, the splendid thing was built. By the time the book was finished, Binh had worked very hard explaining it all to me, the aviation idiot, and he was a very proud author. He would have been an amazing big brother for Siraj. I’m grateful for the time I got to spend with Binh and for the things I learned from him that help me know what children like Siraj need in order to learn a complicated new language.

When Binh’s book was completed, we showed it to the resource lady and to Binh’s teacher. I don’t think they were as excited as we were, but you can’t have everything. I can’t remember whether we finished off Curious George. To Make a Wonderful Plane was something that Binh had written and could read back. It belonged to him. My reward was in watching him carry it under his arm and place it reverently into his desk.

Writing with children is never a straight road. We know that young writers need to read and write about things that interest them. At times this can be a tricky business for teachers to navigate. We like to think we’re encouraging students’ creativity. We balk at the notion of having to emphasize academic writing for our students. We are the millions of liberal arts majors who came to teaching on purpose, because we believed in the possibility of doing something beautiful. But the nuances of artistic genre can be pretty daunting for a student learning English. They become more subtle at various stages as they become more comfortable with a new language. Binh’s book was not a piece of creative writing, per se. Instead, it was a good first opportunity for him to show off his own voice as a writer in the context of a “how-to” piece. Sometimes students who are new to English need to express themselves in functional language situations before they can be comfortable with projects we consider creative. Our opportunity is to be creative in our teaching and in helping them tell us what they know.

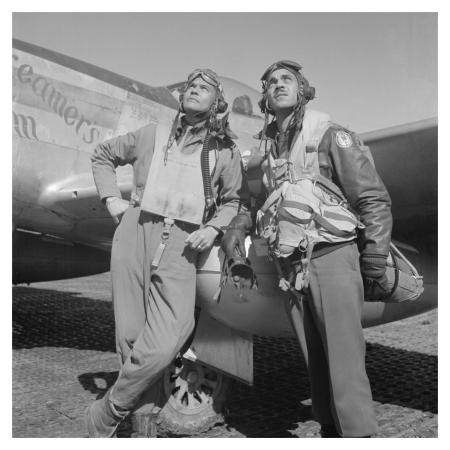

(Photo, public domain image.)

Leave a comment