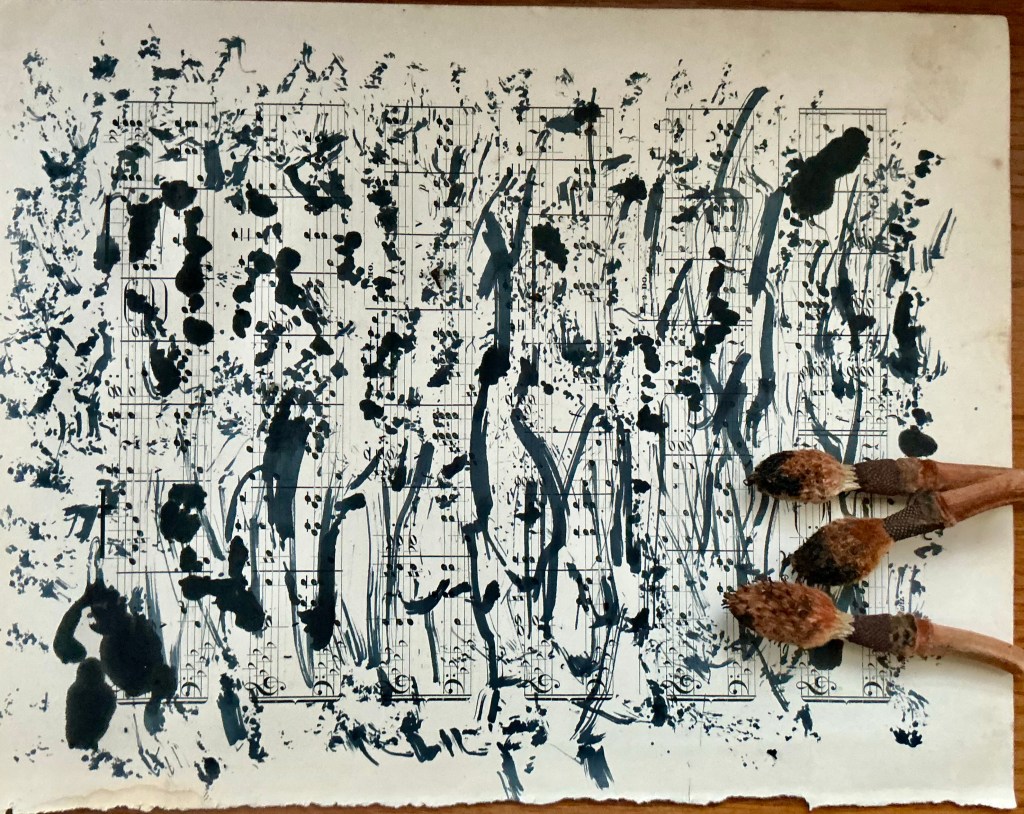

Someone said to me recently that art making is a form of resistance in dark times. This is something I think about often — the importance of creating, of making one’s mark. I think about it whenever I take a long list with me and a big shopping bag and make a trip to one of our local art supply stores. Naturally, when I see the actual price for a #12 Round sable paintbrush or some of that exquisite handmade paper, I end up finding new ways to use what I already have and head home with my bag still folded up in my purse. Or else I’ll see what kind of marks I can produce with some beautiful object I find while out on a walk or learn how to make mountains and rocks in watercolor by scraping my paint surface with an old credit card or a take-out spork. Art doesn’t require fancy materials.

We know that art making makes us feel good. There is the excitement of learning new techniques, the meditative and relaxing indulgence of taking time to practice, and the sense of accomplishment that comes with each level of mastery. There is the pride that goes with making something pretty, and the cathartic release of expressing those feelings that perhaps are not. Art making is good for your brain. It enables neurological development in the young and sharpens mental acuity in the old. Art heals.

I believe we know this intuitively. I think of Matisse when he was ill and bedridden, so compelled to create art that he painted on his walls with an extra-long paintbrush. When Frida Kahlo couldn’t stand, she used a specially designed easel that allowed her to produce magical paintings from her bed. More recently, the writer Souleika Jaouad has shared images she painted while hospitalized to undergo treatment for cancer, powerfully externalizing her illness and her fear. All of these artists knew that mark making could transport them and bring them solace as well as a way to cope with their suffering. But they knew something else, something even the youngest child knows, that is that we need to say we’re here. For young children, drawing is the beginning of message-making, it is literally nascent writing and they are more than eager to show their work! We need to tell someone, even ourselves, that we exist. That in our short existence on this tiny speck of rock in space, we possess some measure of significance, no matter how ephemeral. Art resists our limitations.

Whenever I visit a museum or historical site, I find myself experiencing a deep sense of awe and humility in the presence of art created years, even centuries before this generation. In May of this year, I had the privilege of visiting Pech Merle, a limestone cave in the Lot Valley of southwestern France. Descending into the grotto, we were shown works of art on the cave walls that were painted tens of thousands of years ago. The experience of being in this dark and silent place was overwhelming for its beauty, intriguing history, and anthropological significance, of course. But what I felt, and what I came away with, was an overwhelming sense of connection, of longing, as if these early artists had a need to make their mark, to depict the gorgeous spotted horses and graceful trout of their immediate world and then leave a sign of themselves — a handprint. One artist, believed to be a woman judging from the size of the wrist, had placed her hand on the wall and then, sprayed around her hand with pigment she would have had to hold in her mouth. Astonishing and truly touching to learn, Pech Merle is not the only cave in the world where an artist left behind this kind of hand print. In fact, these markings like this have been found in historic sites from Spain to Borneo, from Argentina to Egypt, and the similarities are startling. These hand prints stand as messages. These artists, some twenty thousand years before the pyramids, before Stonehenge, were signing their work. They were saying to us, “I was here. I lived. This is what I saw that I found beautiful and this is who I am.” Art defies the limits of time.

There is something else to notice in the early art forms. There are no do-overs, no erasers, no cut and paste, no photo editing software, and hopefully no art critics. These artists depicted their world with whatever tools were available to them. Just as the Impressionists became free to depict a world of light at the same time that cameras were available to accurately represent reality, early artists got down to the business of art making without the luxuries we can indulge in today. The work they produced is perfect because it is essentially raw and honest. In getting a chance to view their prints and drawings we are literally witnessing a hand reaching out across time and space from the relative darkness of a cave or grotto.

According to the artist Adrian Elmer, “Art is when a human tells another human what it is to be human.” If this is true, then art is absolutely a form of resistance, when the world seems at times to devalue our humanity. Whatever darkness we may experience at any given time, we still have the power of this most universal form of communication, one that defies time and circumstance. Creating, whether dancing or singing, carving stone or playing a tuba, simply leaving your mark, with whatever you can find, and with whatever quirks or imperfections, is affirmation. So, use what you can get your hands on, or splurge on a fancy new brush once in a while. You’ll feel better. Art resists comparison, critique, and perfectionism. Art making reminds us who we are and creates a powerful message to others that we are here. Art reminds you to take whatever you have and make your mark.

Leave a comment